Sun, humankind & the built form

On the lucky days that I peer up at the sky and see a near perfect sphere of swirling plasma smiling down at me, I feel grateful to be a part of our weird and wonderful world. Since the dawn of civilisation, we as a species have acknowledged the star at the centre of our planetary system as an awesome force, whether it be through the act of endowing it with spiritual significance, or more permanently through the built form. Our changing relationship with the Sun is reflected in our evolving architectonics and is a measure of the progress we humans have made as a community of sentient thinkers.

My two visits to Stonehenge, once in December with my sister and again a few weeks ago, with friends from work (all lighting designers and all equally fascinated by the ancient ring of monoliths and their relationship with the Sun), have encouraged me to do a spot of research on ancient built forms that are reactive to our star, and explore how the relationship between the Sun, humankind and the built form has resulted in the creation of seminal architecture. Below, I’ve chosen to write about three of my favourite built forms from antiquity, and in a few weeks, I’ll follow up with a blog post about three of my favourite from modernity.

A defining feature of Sun-inspired architecture during antiquity is the huge reverence paid to the Sun as a deity. Sovereignty, the power of beneficence, justice, and wisdom as associated with the Sun were whittled down into architectural practice in the form of dwarfing designs, phenomenally formal (as opposed to functional) plays of light and symmetrically balanced compositions.

Stonehenge, Wiltshire, England

William Stukeley in Stonehenge, A Temple Restor’d to the British Druids, 1740, writes of the monument’s relation with the summer solstice, observing that the Sun rose close to the Heel Stone, shining its first rays into the centre of the monument between the horseshoe arrangement. Many years later, in 1963, Gerald Hawkins famously used the Harvard-Smithsonian IBM computer to propose through calculation that dozens of solar alignments could be seen within the arrangements of the stones, claiming that the ancients had used Stonehenge to predict eclipses. Most recently in 2005, Mike Pearson of the University of Sheffield suggested that the structure was in fact used during the winter solstice alone, owing to forensic evidence found in the form of bones and teeth from pigs at Durrington Walls. Their age at death indicated that they were slaughtered either in December or January every year.

I’m no archaeoastronomer, and can only ever hope to understand the solar purpose of Stonehenge through the work of scientists and philosophers. However, as a designer who works in tandem with the Sun, I’m awestruck by the manner in which the Sun seems to make human this gigantic ring of stones. The Sun, viewed through the rocks gives the eye something to focus on, in a landscape that is as vast as it is monotonous. Although one isn’t allowed to touch the rocks anymore, the play of light on the surface of the stones endows them with tactility. It’s through the shadows cast, both on the ground as well as micro shadows between crevices and cracks in the rocks, that the megaliths are brought down to a comprehensible scale. With every movement of our star, a new facet of the stones can be revealed. Stood bathed in warm sunshine, I could imagine ancient island dwellers being drawn into the space during the winter by the long reaching shadows cast between the central Altar Stone and the Heel Stone, marking a path defined purely by the play of light rather than a physical, permanent architectural feature.

El Castillo, Chichen Itza, Mexico

Built more than 1000 years ago, El Castillo, the Mayan Pyramid of Kukulkán, is aligned so that the spring or autumn equinoxes create an optical illusion. As the Sun sets, the north western corner of the terraces cast a shadow on the northern stairway, creating a diamond pattern representing a snake’s body. The shadows cast over the terraces join two huge stone snake heads at the base of the pyramid that appear dismembered for the rest of the year.

El Castillo is a striking example of using natural solar phenomena to architecturally enhance an otherwise seemingly ordinary pyrimidical structure. The fleeting nature of this ornamentation is possible only through the manipulation of natural light with the Sun acting as a distant point source to create a sharp, distinct and transient shadow.

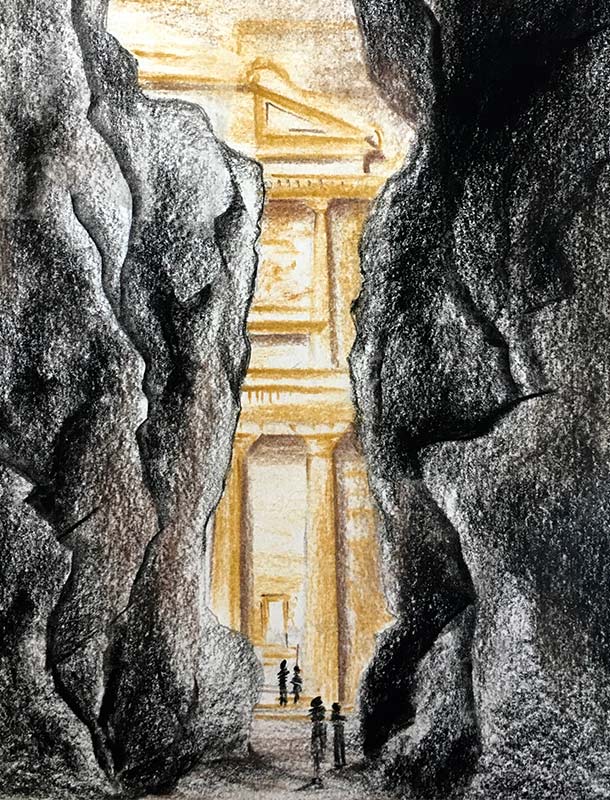

Ad Deir, Petra, Jordan

The wealthy spice traders of the Nabataean Kingdom of Petra ruled modern-day Jordan from the 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD. Much of the city of Petra was constructed with some form of reverence paid to the Sun with spatial orientations of large monuments and sacred buildings aligned with the position of the sun on the horizon.

In a breakthrough discovery, Juan Antonio Belmonte, archaeoastronomer at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands revealed in 2014, the manner in which the winter solstice (which the Nabataeans believed was related to the birth of their main god, Dushara) creates a halo around a sacred podium inside the monument known as Ad Deir, or the Monastery, where the Nabataeans may have held religious activities.

EC Krupp, director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles (who was not part of the Belmonte study) remarked, “This demonstrates we are not looking at an ancient observatory, but at architecture that is in part activated and sanctified by the sky”.

Ad Deir, and more broadly, the city of Petra, finds the Sun central to its architectural agenda. The city is brought to life in bits and pieces through the seasons by organising the architectural layout to reflect solar phenomena. For me, as a young lighting designer, this system of the spatial form following the light is in reverse to the manner in which the architectural process works within the modern construction industry.

The Sun occupies a less venerated position in modern society than it did with ancient Neolithic tribes, pre-Columbian Mayans and Nabataeans. However, we aren’t advanced enough as a society to not feel its effects on our architecture and indeed everyday lives. We do not need solar phenomena anymore to define time for us; however, there is much that we can learn from antiquity with regard to energising our architecture through the clever use of the Sun. Rather than our star being a mysterious, poorly understood and therefore awesome entity, it is a nifty tool in the hands of the 21st century lighting designer and architect.

Sketches: Seraphina Gogate