Lighting Design in the Era of Fake News

It’s no stretch to say that we live in a world full of disinformation. But, somehow, it would be impossible if we didn’t. There are more than 25 billion connected devices in the world, and every person behind them has their own take on what they see and don’t see every day. Since we’re ever more entwined with what’s beyond our own neighbourhood, we generally accept what’s going on “out there” through the lens of who is reporting it to us. What’s difficult, here, is knowing the agenda of the source of information. So, how do we navigate this world that is forever changing? Do we dismiss the views of the certain actors as irrevocably false? Do we view the “realities” of past as falsehood, or as building blocks for a better grasp of the Truth of things? Such misinformation understandably extends to the world of design, and lighting is no exception.

Take, for example, how doctors in the early 20th century suggested that heliotherapy was an effective cure for tuberculosis and rolled out this cure on an international scale. We saw this come about again during the Covid-19 outbreak as many countries’ guidelines suggested daylight exposure as a way to combat the spread of the virus. At the height of the 2020 pandemic, Donald Trump even suggested that we put UV light inside the body as a cure for coronavirus, among other postulations for a cure involving isopropyl alcohol injections and drinking bleach. [It should be noted that heliotherapy is not a cure, but rather a treatment that helps build up the body’s resistance to disease and thus can mitigate devastating effects of illnesses.] In the mid-20th century, as a result of this craze of heliotherapy-as-panacea, we learned that overexposure to UV light caused skin cancer. In the modern day we now struggle with underexposure to daylight due to myriad factors—from an over cautiousness caused by these warnings about skin cancer, our great shift in daylight exposure due to 21st century working patterns, and so on. Due to this, the public now generally suffers from Vitamin D deficiencies among other negative health benefits by shying away from the sun.

Does this mean that scientists, doctors, and politicians are trying to harm us? Are these therapies and cures prescribed to us out of malicious intent or simple ignorance of consequence?

In our role as designers, we need to take this delicate balance of promoting up-and-coming technology against the unknowns of the long-term effects. There’s been a surge in opinion about the disruptive effects of particular blue wavelengths in LED lights, with scientists and laypeople like me questioning if we’ve turned the public into guinea pigs for these futuristic flights of fancy. There are numerous theories which postulate that the extra blue LED light that’s prevalent in our digital devices are over-stimulating us and suppressing our melatonin production. This has been proven and disproven in equal measure to the point that the general public now seems disillusioned to any potential harm thanks to conflicting narratives. A more serious accusation has been made that artificial blue light accelerates macular degeneration. This is yet more complicated by the fact that some cataract lenses don’t provide the same kind of blue light protection that our natural lenses do.

Like the studies on daylight exposure, the technology that we use every day definitely merits a longitudinal study to understand the effects, but the technology has developed too quickly for those results to yet be known. We also have to be diligent about debunking the facts of the past; lighting as its own speciality hasn’t been around very long, and we are regularly in front of clients, engineers, and architects who have outdated notions about how luminaires and control systems work.

Let me please make this clear; that does not make our collaborators wrong nor us lighting designers invariably better-informed. Our role is to educate and inform the team of what we are using in our designs, in the same way that other design disciplines are promoting more sustainable and forward-thinking materials and ideologies for the spaces they want to create. What we can do is scrutinise the information that we are presented by manufacturers, fellow designers, and our array of professional lighting bodies.

We’re currently grappling with advancements in BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy) mesh networking, which is a whole new world of possibility for all of us, and still quite confusing for many. It’s uncharted territory in our world, even though the technology has been used in other fields for more than a decade. We’re also seeing TM-30 data supersede CRI as a way to better express colour fidelity in a larger sample range across the visible spectrum. But what we’re also seeing is number fudging from lighting manufacturers to ensure that they can be specified on a greater number of projects as certifications and aspirations like LEED, WELL, and BREEAM become ever more stringent.

One rather egregious example of this can be found in the completely vital, but often overwhelmingly dry and technical, luminaire catalogue. A lot of luminaire datasheets only report source (chip) lumens instead of delivered lumens, which is a huge issue when trying to choose luminaires based on their efficacies. By only taking the source lumens into account and not the losses from the optics, bezels, etc, you could wind up with efficacies lower than 20lm/w. This is, frankly, irresponsible and a waste of power. Without being diligent in the specification process, a designer could dash any hopes for meeting the most basic of requirements and possibly compromising the certifications for an entire project.

Even more basic than this is the sweeping statement that LEDs never fail, and that by using LED luminaires your maintenance costs will be eradicated. Even though 70,000 hours seems like an awfully long time for a fitting to run before it requires replacement, that figure is calculated using the Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) formula. An asset’s reliability is only as good as the sum of its parts; perhaps the chip itself can survive the 70,000 hours, but if you put the luminaire in a poorly ventilated space, or mangle its cabling while you install it, your theoretical lifespan shrinks considerably. The phrase “to be installed in a well-ventilated, accessible location” should be in every designer’s arsenal.

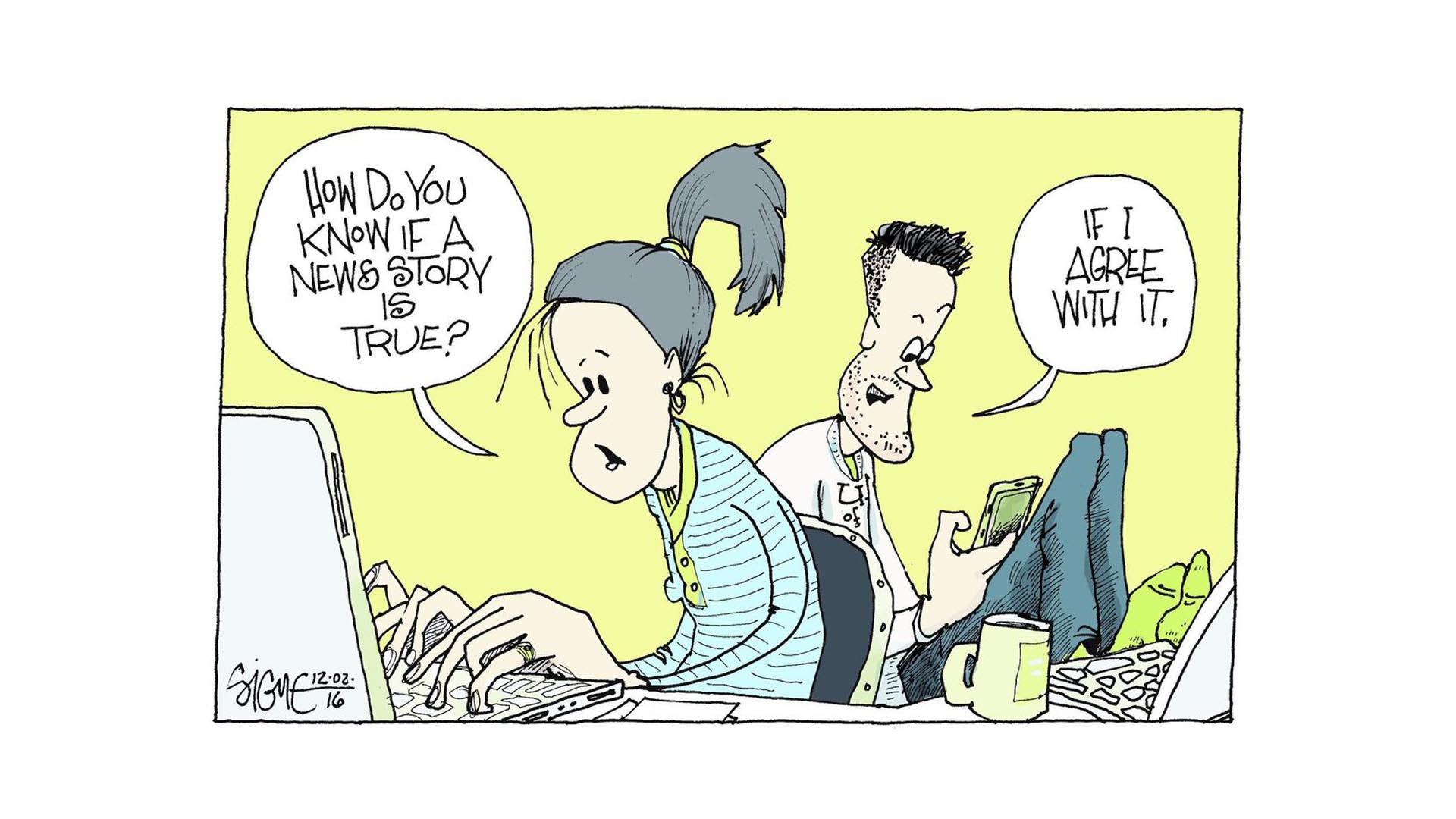

The balance between good intentions and fact becomes a dilemma. Regardless of what the information is—luminaire efficacy, pandemic reporting methodologies, police misbehaviour statistics—we have to question the validity of a) the source and b) the information. We must be intelligent actors in our own lives and our work. And we must never be afraid to ask the hard questions.

Graphic © Signe Wilkinson

Blog post by Kael Gillam